Shattering Romantic Childhood, Creating an Engaged Child: Zenobia’s Genre and Content Analysis

- bsereechaiporn

- Jul 20, 2021

- 20 min read

Updated: Oct 12, 2022

Introduction

This article is part of my study in an International Master's course in Children's Literature, Media, and Culture (CLMC) in 2019-2021. It discusses how the form and content of Dürr and Hornemans' comic-style picturebook, Zenobia (2018), represent and prescribe childhood ideals to promote young children's (pre-teen) awareness and empathy for refugees. The book tells the story of a girl, Amina, who flees from the Syrian war and dies in the sea, breaking the romantic picturebook tradition of protecting child readers from the ugly, cruel world (op de Beeck, 2012). The essay is inspired by Christensen’s (2018) notion that picturebooks’ form and content can maintain and push boundaries of childhood. Leaning on the history of romantic childhood, my analysis notices comic-style picturebooks theory and Nikolajeva’s (2013) cognitive criticism as a theoretical framework.

Hereinafter, I use a structural approach to explore Zenobia’s textual and visual techniques that push the limits of a romantic child and picturebook genre. I argue that its hybrid form of picturebook and comics helps make narratives of refugee crisis more comprehensible and engaging for young children. Meanwhile, its content creates critical thoughts and empathy by juxtaposing a romantic childhood with unromantic reality. In doing so, it breaks through the concepts of romantic childhood, raises awareness of multiple childhoods, fosters empathy for the vulnerable, and endorses a social-engaged child over a romantic child as the ideal childhood.

This essay aims to build on the comic-style picturebook study, which has not yet explored how its hybrid form can help nurture empathy. It intends to understand how such hybrid picturebooks can give children the possibility to engage in a timely conversation about global issues, e.g. the refugee crisis (Amnesty, 2015; OCHA, 2020). The notion is hoped to push the boundaries of childhood, widen the expectation of picturebooks genre, and draw interest upon exploring new literary forms to foster children’s empathy for all.

One of the Rohingya refugee camps in the refugee crisis in 2017

Literature review

Form and content of children’s literature are laden with progressive and retrospective childhood concepts, which can push or maintain the boundaries of childhood (Christensen, 2018). Tensions between narratives of nostalgic and disturbing childhood are prominent in Zenobia, as well as its unconventional form. As nostalgic childhood and picturebook genre were developed in the Romantic movement (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2007), I look into the romantic childhood study to identify the key concepts and boundaries of a romantic child and, from there, try to understand how Zenobia breaks through romantic childhood convention.

In her study on children’s presentations in pre-romantic and romantic literature in European countries, including Denmark, where Zenobia's writers are based in), Kümmerling-Meibauer (2007) identifies innocence and imagination as the core concepts of romantic childhood. Building upon the idea of "childhood innocence", which was gradually formed through the Enlightenment period, the "romantic childhood" sees children as a pure and simple form of mankind; a symbol of freedom from social duties; a kin to nature and divinity; an ideal human with happiness, kindness, and a possessor of virtues that adults had lost. In short, romantic childhood emphasises children’s innocence and imagination rather than their disadvantages and sufferings (ibid.)

An example of the romantic childhood ideal around

the end of the Enlightenment period and the beginning of the Romantic period.

The Sackville Children

Artist: John Hoppner (British, London 1758–1810 London).

Date: 1796. Medium: Oil on canvas.

Although romantic childhood propagated child education and protection in the 18th century (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2007), its idea of childhood innocence so far has been criticized in at least three ways. Firstly, it is criticised for blinding people from the fact that the idea of childhood innocence is not universally adopted or afforded by all classes, cultures, and ethnicities. This ignorance is suspected to result in a demonized perception towards children who do not fit into the ideal, e.g., the non-whites or child delinquents (James&James, 2012; Nel, 2017). Secondly, the belief in childhood innocence is blamed for spurring adults’ discriminating idea that children cannot actively engage in serious matters or even care to learn about real stories (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2007). This bias can lead to adults unintentionally limiting children's participation in the issues that can seriously affect their lives (Gubar, 2013). Thirdly, the concept of childhood innocence likely prompts adults to shield children from some aspects of reality, making them uneducated and unprepared for painful experiences (ibid.)

Under the "romantic childhood" ideal, the focus of child-rearing is also shifted from scaffolding morals and vocational skills to nurturing the child's imagination. As a tool to raise the ideal next generations, children’s literature's form and content have been deeply ingrained with the childhood ideal of their time (Christensen, 2018). Designed particularly to serve young readers since the romantic period (Nel, 2012; op de Beeck, 2012), the picturebook genre is known for and expected to feature reassuring, cute, and simple content, which prioritise literacy promotion rather than serious, depressing thoughts (op de Beeck, 2012). According to Kümmerling-Meibauer (2007), poetry, art, folktales and fairy tales in particular became flourishing in the realm of children's books as adults believed that magical and foreign settings would be more preferable for children's curiosity and could help maintain their childhood wonder. Apart from influencing the content of children's books, the romantic ideal that emphasises a child's distinct mind and imaginative ability can also contribute to the “strict concentration on the child’s perspective and of the narrative technique” which rest on “a simple linguistic style and an imitation of oral storytelling” (ibid., 12).

Comics, on the other hand, does not have the same obligation to preserve childhood purity. From the start, the genre originated from newspaper comic stripes and rebellious underground books, laden with social commentary and sarcasm and catered to the interests of older readers (Hatfield&Svonkin, 2012; Nel, 2012; Nodelman, 2012). However, from the late 20th century, the number of comic-style picturebook and/or picturebookish comic has been increasing. Although both genres similarly narrate stories through text and illustrations, a production experiment on a comics-style picturebook narrative reveals the tension between picturebook’ vocal reading and comics’ silent reading intentions (Palmer, 2014), proving that the two genres truly have different narrating styles. From an educational aspect, wordless comic-style picturebooks are said to help communicate complex narrative and emotions to young children (Beckett, 2012). In a middle-grade classroom study, researchers also found that Tan’s The Arrival (2006), a wordless graphic novel about migrants, help draw students' attention to social issues and encourage their empathetic responses towards the experience of people who are different from them (Rhoades et al, 2015). Yet, ‘how’ picturebooks employs comics form to push childhood boundaries and creates empathy has not been explored. To analyze how Zenobia’s picturebook and comics forms add to one another’s strength in fostering empathy, I use comic-style picturebook theory as a framework.

Tan’s The Arrival (2006) a wordless graphic novel about migrants

read the review of the book here.

The Mixed Format of The In-betweens

Although Zenobia is marketed as “graphic novel” (comics), I am convinced by Chute (2008) to look pass the genre implication of readership, and focus on comics as a form, as comics can be applied to any media and literary types including picturebooks (Chute, 2008; op de Beeck, 2012).

According to op de Beeck (2012), picturebooks and comics are akin in form because they both communicate through graphic narrative, which comprises of words and images that create meanings together. Comics as a form is a word-image hybrid system that register "temporality" in specifically arranged spatial configurations (Chute, 2008). Drawing from Chute’s idea, op de Beeck (2012) suggests picturebooks and comics be evaluated and compared through comics conventions in three aspects: words, images, and the spatial representation of time. However, as space and time are closely tied in comics panels, and as Nel (2012) argues that graphical words can also function as images, I decide to regroup the aspects into two simple and related categories: panels and words & images.

Panel

Both comics and picturebooks similarly illustrate continuous narrative with different bits of information in each panel and use space between fragments to mark time. For example, wider gutters represent longer time duration and the order of panels and text balloons from left to right, top to bottom, signifies chronological order of events (Nel, 2012). Differences, however, largely lie in the numbers of panels per spread and the layout complexity.

Comics pages traditionally comprise of multiple panels and gutters arranged in complex layouts to show narratives of unconnected time and space at once (Nodelman, 2012). To make temporal moments more readily visible, their panels are mostly bordered (Nel, 2012).

The basic anatomy of comics.

Although some picturebooks also have many bordered panels in one spread, most still use borderless single-panel pages and have one gutter where the pages join (Nel, 2012; Nodelman, 2012). The picturebookish panels, thus, create a different experience than comics by blurring one moment into the next or introducing a moment one at a time when turning the page (Nel, 2012). This simpler form helps young readers, whose ability to tell time is still unsteady, comprehend the series of events more easily (op de Beeck, 2012).

Most picturebooks capture one moment at a time.

One example of how picturebooks use several panels in one spread.

Words & Images

How the two genres place their words and images on a page is traditionally different. Comics commonly superimpose words both outside and within the image (Nodelman, 2012), creating several kinds of tension that open to various ways to read and interpret (Nel, 2012; Nodelman, 2012). Picturebooks, on the other hand, tend to separate images and words by placing words on a clear space for easy reading (Nodelman, 2012). Furthermore, comics’ words and images usually work together in the less instructive form to describe “more specific information about what is happening than picturebooks do”, such as splitting a moment into various panels that show the same character from different angles to emphasise his expression and emotional state (ibid. 443). Their complex relationships prescribe readers to read back and forth between text and image to gather all messages (ibid.). Meanwhile, textual-visual relations in picturebooks tend to be more illustrative (Nel, 2012) and commonly allow, or instruct, readers to read text and then image to find variations of meaning or the information described in the text (Nel, 2012; Nodelman, 2012).

The Heart-wrenching Content

According to Nikolajeva’s (2013) article on cognitive criticism, all social skills are not innate but require training to become functional. Empathy, or the ability to understand other people’s emotions, is one of those skills that require training from the youngest age and reading is one way of doing it. Through reading, young readers are put in front of several hypothetical situations that push them to observe and recognise different kinds of emotions and problems and ruminate on how these puzzles can be solved. Picturebooks, in particular, can largely help young children learn about emotions and develop empathy. With large images on each spread, picturebooks can show various emotions and expressions graphically, without requiring children to be able to read. The huge illustrations allow picturebooks to put emphasis on characters' eyes and mouth, which are human’s prominent features to reflect emotions. Picturebooks also use many artistic tools, e.g., color, emanata, symbol, characters’ size and position, etc., to give emotional cues and label emotions with words to help children articulate them later. By showing several characters’ expressions simultaneously and sometimes ambiguously, picturebooks train readers to mind-read people from different angles and grow their empathy for those who are similar to and different from them. Reading text and image in the simple form of picturebooks also scaffolds young readers to read the more complicating situations in other forms of literature, such as comics and novels.

Hereafter, I observe Zenobia's plot, characters, and other narratological elements; comic and picturebook constructs (e.g., gutter, panel, word-text relation); and visual techniques (e.g. color, angle, composition, etc.); and try to understand how these can help readers "train" their empathy. As reader response is not in the scope of this essay, the analysis rests upon only the text’s potential for implied readers and does not discuss readership response.

Me being traumatised by reading Zenobia

over and over again for this analysis.

The Analysis on Zenobia's Form

This part of the analysis demonstrates how Zenobia's panels and the combination of words and images push both the boundary of the picturebook genre and the romantic childhood ideal, while rousing young reader's empathy for child refugees.

Panels

Zenobia ’s panels have two types: picturebook-like and comics-like. The pages with picturebook-like panels take up a quarter of all the book’s spreads, showing one full-bleed panel per page. The pages with comic-like panels, having bordered panel(s) on white pages, are mostly presented (Nel, 2012), however, never with over three panels per page.

Zenobia's picturebook-like panels

Zenobia's comic-like panels

Three is the maximum number of panels per page in Zenobia

All the bordered panels are rectangular, separated by horizontal and vertical gutters. There are only four pages that superimpose a couple of small panels over a full-bleed page, blending the comics and picturebook forms (Nel, 2012), and just one page showing a small circular panel with a clos-up of Amina’s mother’s face when she reminds Amina about Queen Zenobia, the girl's role model.

One of a few pages that place panels on top of a full bleed page.

The only circular panel in the book.

As space in comics and picturebooks represents time, the panels’ simple shape and division, which are easily read from left to right, top to bottom like in picturebooks, can help novice readers with a shaky time-telling skill to read and develop to more complex visual reading skills (op de Beeck, 2012).

The two types of panels in Zenobia differently provide readers visual cues that engage them in emotional interpretation, an important skill to foster empathy (Nikolajeva, 2008). As comics-like panels are small and many of them can be arranged in one spread, together they can display different information simultaneously to compare and contrast, or they can repeat the same information differently to specify moments (Nodelman, 2012; Nel, 2012).

Zenobia uses these comics advantages to draw focus to characters’ subtle emotions in four ways. Firstly, comics-like panels give a sudden closeup shot of a character to make his/her eyes and mouth, which reflect emotions, easy to see (Nikolajeva, 2008), e.g., Amina’s disbelief eyes and gaping mouth when she is thrown off into the sea (12).

One of the pages that show close-up shots

that capture characters´ facial expressions.

Secondly, in splitting one image into multiple panels on one page, the panels highlight specific actions or reveal the contradiction between facial and body expression. For example, the image of Amina on a boat (7) is split in half; the upper panel shows her expressionless face, while the lower panel reveals her worry by centering readers’ gaze at her gripping hand on her arm, implying not only her nervousness but her attempt to be brave. The divided panels guide readers’ eyes to linger on the content in a specific panel to extract complicated meaning (Nel, 2012). This helps readers comprehend contradicting and ambiguous emotional presentations more easily (Nikolajeva, 2008).

(Right page) while the upper panel shows Amina's expressionless face,

the lower panel reveals her worry by centering readers’ gaze

at her gripping hand on her arm.

Thirdly, comic-like panels split an action into small moments to suggest small movements and expressions (Nodelman, 2012). For example, in the scene in which Amina decides to flee, her hand stretches out to grab her uncle’s in three slightly different panels, showing her slow movement that signifies reluctance (56-57). Meanwhile, drowning Amina is shown in three panels with the same pose, zooming into her bubbling mouth which signifies her last breath and creates a suffocate feeling in readers’ mind (34-35).

Amina's reluctance is shown in three slightly different panels.

Amina's slowly drowning is depicted in three panels,

zooming in bit by bit to create a suffocate feeling in readers' mind.

Fourthly, comic-like panels represent a shift from the third-person to the first-person point of view, allowing readers to see through Amina’s eyes and creating an immersive effect. For example, when waves throw Amina out of the boat, the sun and waves above her head are shown from her viewpoint in one small panel before she falls (12); the following black panels represent her losing consciousness underwater before having flashbacks (28-29). Subtle emotional presentation and immersion can support readers in understanding refugees’ fear and despair, by looking close up to their body movement and facial expressions, imagining their physical feelings and seeing from their point of view (Nikolajeva, 2013).

Amina's viewpoint showing the sun and bubbly waves she sees

before she falls.

Black panels represent Amina losing consciousness underwater.

On the other hand, full-bleed picturebookish panels display emotions in regards to situations happening around the characters. The focus on surroundings is important because to sympathize with others, one needs to understand their contexts to comprehend their motives and choices that make them do what they do (Nausbaum, 2003).

Full-bleed panels in Zenobia are used to engage readers in interpreting emotions and understanding characters’ context in three ways. Firstly, the abrupt change to big borderless panels gives readers a sudden emotional shift and stresses the unpredictability of life. For example, when Amina goes out of her house and sees the war broke out (47-49), and when waves wrecks the refugee boat (78-79), a sudden change from multiple comics-like pages to full-bleed wordless spread re-creates in readers’ mind a similar tragic surprise that refugees experience (Nikolajeva, 2013).

Amina goes out of her house and sees the war broke out.

Secondly, picturebook-like panels in Zenobia enhance refugees’ powerlessness in war and refuge. There are two long sequences of full-bleed panels in Zenobia. One shows Amina’s journey through war zones, in which her body gradually reduces in the increasingly larger ruined landscape (58-69); another shows her sinking and dying alone in a vast calm sea (80-91). Depicting the refugees being shrouded in the vast lonely settings and deserted both on land (by their country and other countries) and in the sea (nature), these big panels instigate the feeling of loneliness and defenseless that readers are encouraged to empathize with.

Big panels underscore that refugees are deserted by their surroundings.

Thirdly, picturebook-like panels in Zenobia put emphasis on the key scenes that readers can compare to explore the themes of wars and refugees further. For example, by juxtaposing the warrior queen Zenobia’s glorious pose on the majestic landscape of Rome (40-41) with shocking, small Amina surrounded by the city ruins (48-49), the book leads readers to ruminate on how cruel and devastating actual wars can be. Unlike in the glorious legend, wars kill not only lives but also all hopes and dreams. The loss of hope and innocence is signified by the sunken ship called Zenobia found at the bottom of the sea (82-89).

The contrast images of wars in a childhood tale and in reality.

Words & images

Picturebooks and comics similarly tell stories with words and images. However, the simplicity of layout and eye movement in reading the two genres are different in degree (Nodelman, 2012; Nel, 2012). Similar to traditional picturebooks, where words superimpose images in clear space, Zenobia separates words from images with a white frame to make reading easy for children (Nodelman, 2012). With few exceptions, each panel has only one or two word frames. The frames are placed mostly on the top-left corner to instruct readers to read the text first and look for more information in the image (Nodelman, 2012). Speeches are also not separated from the narrative in speech balloons like comics tend to do (Nel, 2012). However, the question of who says what may hardly arise as a panel shows only one person per speech.

The book does not use word balloons for characters' speeches.

Textual-visual interplays in picturebooks and comics are also similar as they use words and images to complement and counterpoint one another to communicate meaning they cannot do alone (Nel, 2012; Nodelman, 2012; op de Beeck, 2012). The words in Zenobia, however, is muted under visual narratives, as the book shows no verbal and grammatical complexity, or the variety in typeface and font size.

The book is nearly wordless, and when a panel has words, the words tend to add more information to the image which can already be understood by itself. For example, when Amina and her uncle converses about fleeing, we can deduce what they are arguing from their facial expressions and the images in the panels (54-55).

Amina and her uncle arguing about whether she should leave the house or not.

Sometimes words also help explain what images cannot describe and make them easier to comprehend. For example, when Amina sinks in the sea (34-35), without words readers will not know that her zoomed up lips means she is tasting the sea saltiness and be reminded of dolmas, the food she made with Mama. This illustrative function is prominent in picturebook’s narrative, which aims to accommodate child reading (Nodelman, 2012). By downplaying the words’ importance and presenting images that are easy to understand, Zenobia disengages shared reading function from its picturebook form and gives agency to children to read and comprehend the work on their own (Todres&Higinbotham, 2016).

By combining two conventions of panel usage, words, and images, Zenobia emotionally engages children in a refugee topic in two aspects. Firstly, its simplistic form that leans on simple visual narrative allows children to read and understand content about refugees, a serious topic that the picturebook genre has been avoiding and some adults may hide from their child (Nel, 2017; op de Beeck, 2012). The integration of comics to a form that children are familiar with, like picturebooks, can scaffold and prepare their visual literacy for more complex graphic narratives as they grow. Secondly, the hybrid form provides various tools to engage children in learning complex emotions and fostering their empathy, from noticing facial expressions and body language, to feeling, seeing and perceiving the surroundings like a child refugee.

The Analysis on Zenobia's Content

This part of the analysis discusses how Zenobia’s textual and visual content maintain and break concepts of romantic childhood to foster empathy in child readers. Picturebooks, like other literary works, can elicit emotions from readers by representing reality (Nikolajeva, 2013). However, misconceptions of what a real world is like may arise when literature does not present the whole truth or keeps displaying the ideal while ignoring other aspects of reality.

Lively, imaginative, and innocent childhood is an ideal that has been represented in picturebooks since the Romantic period (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2007). A happy childhood where children do not work, enjoy the imaginary world, and be spared from cruel conditions of life may be reality in privileged families who can afford to make their children's lives comfortable. However, there are many more kinds of childhood than that, which have not been equally represented. The inequality of representation stems from a romantic idea that picturebooks should protect and prolong the short period of blissful, ignorant childhood by entertaining the young, affirming security, and avoiding any disturbances (ibid.)

Zenobia first breaks through this romantic norm of picturebooks by speaking for underprivileged children through the form that young children can easily comprehend. The story is told by Amina, a child refugee, who is roughly less than ten years old, as seen in one panel that she can hide in a narrow gap under a chair (25).

Amina playing hide and seek with her mum.

Judging from her body size, she should be less than 10 years old.

Amina's story comprises three interwoven narratives: her present, past, and imagination of Queen Zenobia, who represents her hope of growing up as a strong and courageous woman. The age of a protagonist commonly signifies the age of the book's implied reader since similarities can help engage readers in the character’s life. However, the life of a refugee protagonist can be too different and hard to comprehend from the viewpoint of well-off target readers, who afford the book and may be living a better life, if not an ideal life. To spark empathy, the representation of a romantic child ideal is, thus, required to create a common ground between the readers and the character (Nikolajeva, 2013).

The three narratives in Zenobia are presented based on many concepts of romantic child ideal. Amina's past narrative is depicted in warm sepia color, symbolizing the nostalgic childhood which harks back to a romantic concept that childhood is the absolute happiness that adults can never return to (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2007).

In this narrative, Amina is shown to be a lively child who loves playing hide and seek with her mom (20-27). Life normalcy, happiness, and security are displayed as Mama always hides at the same spot so that the girl can find her. The warmth and love between the mother and the child are enhanced with three separated panels, centering at their loving faces and hugging arms (24).

Amina's happy childhood.

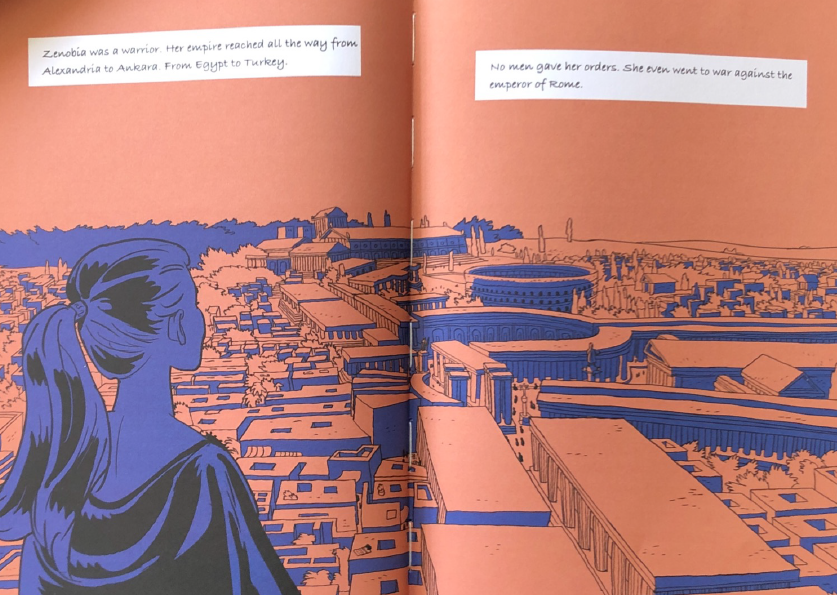

As a romantic child, Amina is imaginative and loves art. She makes imaginary coins for her kingdom like Queen Zenobia of Syria, a folklore heroin whom she cherishes for her strength and bravery (73). Amina’s love for folktales also corresponds to a romantic idea that children like folktales because the foreign settings appeal to their imagination (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2007). The idea is enhanced as Amina’s narrative about Queen Zenobia is vibrantly depicted in red and blue, signifying both female empowerment and the girl’s vivid imagination.

The glorious folktale narrative is depicted in bold colours.

The unromantic part of Amina’s childhood is subtly revealed when she and her mom make dolmas with rice and salt filling (30-33). Mama tells her about other nutritious ingredients they should have used, implying the family’s poverty. Unlike a romantic child who can devote to play and depend on adults. Amina helps her mother with housework and is taught to be an independent girl who can take care of herself like Queen Zenobia (37).

Food scarcity in Amina's household during wartime.

Despite not showing to be affected much by poverty, Amina is not blind to it and is observant enough to see Papa’s lie and Mama’s cry. The parents’ attempt to hide sadness from Amina is depicted in close-up shots showing their delicate expressions: Papa smiles with sad eyes and Mama closes her eyes and cries a small teardrop (33). The dark shadow around these realistic, minimal expressions helps alert children to be keen and sensitive to others’ misery, which can be hidden due to shame, fear, or other reasons (Nikolajeva, 2013).

Hidden sadness is emphasise in the narrative of Amina's romantic childhood.

As romantic representation tends to overlook children’s disadvantages and rather emphasize their universal romantic qualities, especially their innocence (James&James, 2012; Nel, 2017). Amina’s needy childhood extends the concept of a romantic child by noticing both her romantic traits and her hardship. Thus, the book claims that all children from different backgrounds, innocent or not, are children alike.

As the story progresses, Amina’s childhood gradually contrasts with all the romantic ideals. The girl grows from a disadvantaged-yet-lively child in a loving family to an orphan refugee who boards a boat alone to escape the war. The full-spread glorious landscape of Rome with Queen Zenobia’s back showing to readers (40-41), contrasts with the ruined neighborhood Amina finds herself in (48-49).

Comparing the two spreads, the book suggests that war glory in folktales is just a mistaken fantasy. A journey to a foreign land is not fun or magical as a romantic child would have liked. Rather, it is scary and deadly for a refugee child.

Amina’s present-time narrative, which is depicted in realistic colors, is repeatedly juxtaposed with her imagination and past narrative and consistently snaps readers out of ideal concepts to face the reality. The reality of child refugees is that child power exists only in imagination, as Zenobia turns out to be just the name of a sunken ship in real life. A play of hide-and-seek is not fun when no one can find you in a vast sea. Poverty is not eased by imaginative coins. Adults cannot protect you; they cannot even save themselves.

A sunken ship, Zenobia.

No magic or divine beings can help Amina; even nature is not in her favor. If empathy is fostered through a representation of reality (Nikolajeva, 2013), empathy in Zenobia is built from the recognition of the real children in actual crisis, not an ideal protagonist in a metaphorical situation.

Moreover, the book engages readers in taking action by repeatedly emphasize Amina’s vulnerability. For example, it shows Amina, little by little, shrinks among the ruins (56-65) and in the sea (70-71) to stress her tininess and fragility and her need to be saved. As the reader is the only one in the story who can see Amina’s spoken fear when she acts brave (74) and hears her drown whisper, “Find me!”, when she dies (92-93), they become the witness of a tragic childhood that exists in real life and may be inspired to translate the recognition into actions to save suffering children in the real world.

Discussion and Conclusion

This essay discusses how Zenobia represents both romantic and un-romantic childhoods and fosters children’s empathy with war refugees. It argues that Zenobia intends to enhance children’s ability to understand complex, negative emotions and situations by simplifying comics form to communicate a serious topic to children and providing a variety of emotional cues, which can be useful for creating emotional literacy and empathy.

Content-wise, the book employs a romantic ideal to connect the life story of a refugee child to its readers, before invalidating all the romantic concepts it has referred to. However, Zenobia does not deny the romantic idea to protect children’s happiness and well-being. It rather pushes the ideal foward to involve children of all socio-economic backgrounds and urges readers to notice and protect all forms of childhoods.

This essay, however, is still limited to the form and content analysis of a comic-style picturebook. Further research can be on how such a hybrid book actually works with child readers. It is also interesting to see how refugee children or refugee communities perceive refugee-themed books like this. To what extent do refugee stories written by non-refugees reflect the reality? Most importantly, how can we include actual child refugees in speaking for themselves to children in other communities around the world?

Reference

Primary Text

Dürr, M. & Horneman, L. (2018) Zenobia . New York: Triangle Square.

Secondary Text

Amnesty International (2015) “Global refugee crisis requires a paradigm shift on refugee protection Amnesty International recommendations to UN Member States 22 September 2015” Avalaible from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/events/ga/2015/docs/statements/AmnestyInternational.pdf. (Last accessed 15th June 2020).

Beckett, S.L. (2012) ‘Wordless Picturebooks’ In: Crossover picturebooks: a genre for all ages , Routledge, London;New York. pp. 81-146

Christensen, N. (2018) ‘Picturebooks and Representations of Childhood.’ In:

Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. & Taylor & Francis Group 2018, The Routledge companion to picturebooks , Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, Abingdon Oxon. pp. 360-370

Chute, H. (2008) "Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative", PMLA, vol. 123, no. 2, pp. 452-465.

Gubar, M. (2013) "Risky Business: Talking about Children in Children's Literature

Criticism", Children's Literature Association Quarterly , vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 450.

Hatfield, C.&Svonkin, C. (2012) “Why Comics Are and Are Not Picture Books: Introduction”, Children's Literature Association Quarterly , vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 429–435.

James, A. & James, A.L. (2012) ‘Innocence.’ In: Key concepts in childhood studies , 2nd edn, SAGE, London;Los Angeles, Calif.

Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (2007) ‘Images of Childhood in Romantic Children’s Literature’. In Gillespie, G., Engel, M. & Dieterle, B. 2008, Romantic prose fiction, J. Benjamins Pub. Co, Amsterdam;Philadelphia. pp. 184-202

Nausbaum, M.C. (2003) ‘Chapter 3 The Narrative Imagination.’ In: Cultivating humanity: a classical defense of reform in liberal education , Harvard University Press, London; Cambridge, Mass. pp. 85-112.

Nel, P. (2012) “Same Genus, Different Species?: Comics and Picture Books”, Children's Literature Association Quarterly , vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 445-453.

Nel, P. (2017) ‘How to Rad Uncomfortably.’ In: Was the cat in the hat black? : the hidden racism of children’s literature, and the need for diverse books . New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 67-106

Nikolajeva, M. (2013) "Picturebooks and Emotional Literacy", The Reading Teacher , vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 249-254.

Nodelman, P. (2012) "Picture Book Guy Looks at Comics: Structural Differences in Two Kinds of Visual Narrative", Children's Literature Association Quarterly , vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 436-444.

OCHA (2020) Rohingya Refugee Crisis. Avalaible from: www.unocha.org/rohingya-refugee-crisis . (Last accessed 15th June 2020).

op de Beeck, N. (2012) “On Comics-Style Picture Books and Picture-Bookish Comics”, Children's Literature Association Quarterly , vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 468-476.

Palmer, R. (2014), "Combining the rhythms of comics and picturebooks: thoughts and experiments", Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics: Watch This Space: Childhood,

Picturebooks and Comics , vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 297-310.

Rhoades, M., Dallacqua, A., Kersten, S., Merry, J. & Miller, M.C. (2015) "The Pen(cil) Is Mightier than the (S)Word? Telling Sophisticated Silent Stories Using Shaun Tan's Wordless Graphic Novel, the Arrival", Studies in Art Education , vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 307-326.

Todres, J. & Higinbotham, S. (2016), ‘Participation Rights and the Voice of Child.’ In: Human rights in children's literature: imagination and the narrative of law , Oxford University Press, New York. pp. 33-57

Comments